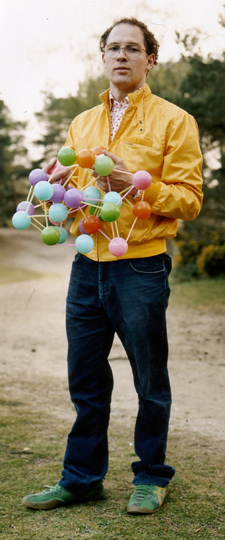

Musical & Mathematical Abstractions… and Table Tennis: A Rap Session with Daniel Snaith of Caribou

Not many people will ever use the phrase “Overconvergent Siegel Modular Symbols” in a sentence, but that’s one thing that makes Dr. Daniel Snaith, the mastermind behind Caribou, who happens to have a Ph.D. in number theory, a one-of-a-kind neat dude you might take underwear shopping while casually dissecting the essence of reality. Here, all the questions planned regarding favorite foods and Beach Boys were soon forgotten, and instead we slipped into the mud and spent some time digging wormy abstractions.

Not many people will ever use the phrase “Overconvergent Siegel Modular Symbols” in a sentence, but that’s one thing that makes Dr. Daniel Snaith, the mastermind behind Caribou, who happens to have a Ph.D. in number theory, a one-of-a-kind neat dude you might take underwear shopping while casually dissecting the essence of reality. Here, all the questions planned regarding favorite foods and Beach Boys were soon forgotten, and instead we slipped into the mud and spent some time digging wormy abstractions.

I have never seen you live and the videos on your MySpace page don’t work. Every one I pressed was sorry no longer available. I took it as a sign that I wasn’t going to watch any Youtube videos. What is the audience like at your show?

We get all sorts of stuff actually, from standing and staring kind of serious music nerd crowd, which I can’t complain about because I definitely am a serious music nerd probably if you saw me in the audience. We also get wild hippie dancing, people on acid and other kind of drugs, and I love those people too. Then we get, in the UK especially, severely drunk people who are more into participating by yelling stuff out and getting right up there in your face, which I also quite like. I can see the appeal to watching a kind of show like ours in any of those ways, just standing back and listening, or I’m always definitely pleased when people get into it or are a little drunk or inebriated in some way or another.

Aside from the visual projections, I read that you change the way songs are presented when you play them live with the band as opposed to when you record by yourself. What’s different?

The main thing people would notice is the intensity. Some of the songs we stick quite closely to the arrangement on the record. But even if we think we’re playing them like the record, the fact that there are two drum kits bashing away, lots of live dynamic in the instruments on stage, makes it a more in your face, aggressive, more visceral experience than listening to the record, which is maybe more subdued, more laid back sounding. We can make a big wall of sound and make a lot of noise up there. A lot of the songs tend to extend and go into big psychedelic jammed out sections, and evolve as we tour, so things head in that direction.

You toured for a year straight, that’s a lot of band time. Does playing with the band affect your writing when you return to your lair?

It can go either way. Sometimes, I start with a loop or an idea and immediately I imagine playing it live, and that experience of what makes the music exciting to play live dictates how the song goes. Sometimes when we’re on tour, I’ll come up with an idea that I think, “Man we’ll never be able to do that live but when I get home and start recording, I’ll try that in the studio.” So that’s the thing I like about this bipolar way of recording. It benefits from us playing live and me thinking about those things but it also isn’t limited by that. It’s not like the music has to be recorded in a way that it can be played live.

What are the “if we can do that…” moments inspired by?

Almost always my music is inspired by playing or tinkering around on instruments or listening to other music. As much as I like other kinds of art forms, my experience of those things doesn’t end up in my music so much. The reason I love music is the sheer excitement I get out of sound and melody and production. Just detached from the real world or other things.

I was reading a heady book called Music, Sound and Sensation, so I’d like to get a little weird. Basically, your experience of music doesn’t seem to be language based. If music is operating outside of reality in terms of inspiration then that—reality—is not what you’re communicating to, like the passage of information as opposed to that of expression.

Definitely. The way I record, I’m by myself. I have a musical idea, I don’t have to think of it in linguistic terms, I just directly try and realize that idea. I think in music, in terms of sounds and then I make sounds, so it doesn’t have to be translated through any other kind of medium, whether it be linguistic or influenced from some idea from visual art and then transferred into music. It’s such a directive session with sound itself and with melody and harmony. A composer a couple hundred years ago would have had a musical idea and then kind of translated it into some notation or whatever. I don’t even need to do that. I mean, things end up fitting some kind of chord sequencey format and it could be written down but there’s no translation between having an idea and trying to play it.

Do you think music is a language or is it not a language?

It’s not a very efficient language. That’s the thing I like about it. People often get the opposite impression of what I think. I’ll often think, oh the song I made is really melancholy, and then people turn around and ask me, why is that song so joyous sounding. And I kind of like that mistranslation. People can pick up on totally different aspects. It’s a very potent way of communicating in that people often have very strong emotional responses to music, the way they don’t even necessarily to language.

Do you think your relationship to music has anything to do with being a math guy?

Not in any conscious way. There’s no mathematics in the music. At the moment I’m talking about it using this kind of pseudo-academic way or whatever! But when I’m making music, I’m not thinking about it at all. I’m just doing it. It’s a very immediate emotional response. It’s about being excited, being happy to be doing it. The two things I’ve always loved doing, being mathematics and music, there’s a level of abstraction to both of them. There’s an individual nature to the way I’ve done both but not in the way that people would say, so and so is a mathematician and also a musician. I think they’d imagine a very precise robotic way of making music and that couldn’t be further from the truth.

So it’s like you’re satisfying your two halves independently.

You know, I’ve never seen them as being connected, but then I enjoy them for some of the same reasons.

I wonder what it is that applies to both. Maybe it’s non-languageness? I mean, with math you’re communicating, well no, I guess you are not communicating anything. What’s the point of math?

Well, the kind of math I do, it’s this kind of pure mental pleasure of playing around with abstract ideas. Maybe the thing I like about both of them is this sense, whether it’s an illusion or not, that there’s some sort of elemental kind of truth in a beautiful song and an elegant mathematical concept. You feel that you’re going to fumble around and discover something that’s truthful in some way that, as you say, isn’t filtered through language, or filtered through something imprecise, it’s something very kind of precise.

If your music’s more about the sounds and the melodies you can build, where do the lyrics come from? Do you look at them musically?

This last album, Andorra, is the first album where there’ve been actual songs. I make the song instrumentally. I figure out all the melodies and harmonies and have the arrangement planned out in my head and then I translate it, and say, this song feels kind of melancholy or joyous and then write the lyrics to sketch out the situation, kind of simple, two people falling out of love or falling in love, that mirrors what the emotion in the music said to me. The melody comes first and the lyrics are a translation of that melody.

You’re a listener. You put yourself in that intermediary spot.

For some people the thing that makes them emotional about music or connects to them is the lyrics. Me, I never know lyrics to any songs. Even the most popular songs. I listen to it as sound. Songs are just as likely to make me want to cry or make me happy but it’s because of the melodies or the harmonies. The sound is affecting me rather than, “this is a song about being sad.”

It’s almost like the effect of a silent movie. The scene shows something sad but the music is driving towards this other point so there’s this confusion of feelings…

Yeah! Sorry to interrupt. I actually like that in music, where the lyric has a little bit of both, it has melancholy and a bit of happiness or there’s a mismatch of both in the music. That can often be interesting. There can be two different kinds of emotions in the two things and they don’t match up. [Clangs a cymbal twice]

When’s the last time you said “Wow?”

I know what it was. Maybe this isn’t in a profound way, or maybe it is. I’ve been working on my table tennis game recently. I’ve been playing against an old friend and also a new friend who seems like an old friend from Fuck Buttons who we toured with in the Spring. They’re both diabolically good. I’ve been trying to become as good as them but I’ve often said, “Wow,” in response to their smashing the ball at me.

That’s a good wow situation.

Caribou play(s) the 2008 Download Festival this Sunday at the Gibson Amphitheater along with The Jesus and Mary Chain, Gang of Four, Brand New, Mutemath, Yeasayer, Ghostland Observatory, M83, Flosstradamus, RJD2, Mates Of State, The Duke Spirit, The Night Marchers, Blitzen Trapper, Tapes ‘N Tapes, Datarock, The Parlor Mob, Kaki King, Vedera, William Fitzsimmons and De Novo Dahl.